Free Peer Review Article on Social Dominance Theory

1. Introduction

In recent decades, dearth, war, political conflicts and environmental factors in critical areas of the world have increased the flow of immigrants into different European countries. In addition, the bewitchery engendered from the economic prosperity and the relative political stability of some European countries has raised this period of clearing. Thus, in 2016, iv.i% (20.1 million) of the European population was composed of minority groups of immigrants (EUROSTAT 2017). Likely, immigrants' integration represents one of the most important challenges to our globalized society in the gimmicky age. Clearing and integration policies need to be developed in lodge to prevent intergroup conflicts. Indeed, the time to come of EU society is strongly related to the adaptation and integration of immigrants and their children. This cultural transition's process has been widely recognized as a social sciences procedure that encompasses different fields such as social psychology, sociology and economics as well as politics. One of the aims of this report consists of investigating some social-psychological factors that could play a key function in the agreement of the phenomenon related to attitude towards immigrants.

A relevant factor that has been traditionally related to discrimination, prejudice and stereotyping of minority groups is the social authorisation theory (SDT; Pratto et al. 1994; Pratto et al. 2006; Sidanius and Pratto 2001; Sidanius et al. 1994b). Such a theory posits that individuals showing college levels of social dominance orientation (SDO) as well report a highly stratified and hierarchical vision of society. In other words, social-ascendant people support the idea that intergroup and interpersonal relationships should be highly hierarchical, while individuals showing lower levels of SDO approve and support equality-based intergroup relationships. Social-dominant people preferring group-based hierarchies emphasize antagonism, inequality, and the supremacy of some groups viewed every bit ascendant over those dominated. Based on these assumptions, previous inquiry has shown that social dominance is related to several outcomes such as prejudice, discrimination, negative reactions to people belonging to a low-condition group, and back up for warfare, as well as cruel initiatives (eastward.g., Pratto et al. 1994; Sidanius et al. 1994a; Sidanius and Pratto 2001). Sidanius and colleagues take pointed out that a crux in the SDT is the competitive vision of the world characterized by lack of empathy, scant business for other individuals, and unwillingness to identify with them (e.g., Pratto et al. 1994; Sidanius et al. 2013; Sidanius et al. 1994b). Thus, one could suppose that social-dominant people tend to view the globe equally a dog-eat-dog surround (Pratto et al. 2006).

Let me now plough to the relationship between SDO and the negative attitude towards immigrants. Some authors have highlighted a human relationship between SDO and negative reactions to immigrants (eastward.chiliad., Costello and Hodson 2010, 2011; Guimond et al. 2010; Thomsen et al. 2008). In particular, Thomsen et al. (2008) postulated the "status boundary enforcement hypothesis" claiming that: "SDO should exist associated with aggression confronting immigrants who do assimilate into the dominant culture considering this blurs existing status boundaries between groups" (p. 1455). More than specifically, it would seem that SDO is more than strongly associated with negative reactions towards immigrants when they are eager to assimilate into the dominant civilization. By dissimilarity, a social-dominant disposition would seem more weakly related to negative reactions towards immigrants that adopt the cultural isolation. In a subsequent study, Guimond and colleagues corroborated this link between SDO and negative attitude towards immigrants (Guimond et al. 2010). In this vein, Costello and Hodson (2010, 2011) showed that higher levels of SDO are related to greater resistance to help immigrants needing help and prejudice towards immigrants, as well every bit their (de)humanization. Even though previous literature has empirically established a link between SDO and negative attitude towards immigrants (e.g., Guimond et al. 2010; Costello and Hodson 2010, 2011; Thomsen et al. 2008), petty is known nigh potential factors that could play a relevant function in this relationship. The main aim of this written report consists of shedding low-cal on potential underlying factors in the association between SDO and negative mental attitude towards immigrants. At that place is prove that citizens' happiness could play a relevant role in fostering equality and that it is associated with important social indicators (Flavin and Radcliff 2009; Flavin et al. 2011; Oishi et al. 2018; Radcliff and Shufeldt 2016).

Happiness has been considered to exist ane of the most relevant outcomes of human life (Diener et al. 2015). Information technology could be considered one of the primary sources of wellbeing (e.thousand., Diener and Biswas-Diener 2002). Indeed, several studies take pointed out that individuals' happiness is related to several achievements in life such as marriage, a comfortable income, career success, a long life, life satisfaction, reduced job stress, and proficient mental health (e.g., Diener et al. 2017; Mastekaasa 1994; Diener and Biswas-Diener 2002; Naseem 2018; Clark et al. 2018; Jebb et al. 2018; Walsh et al. 2018). With respect to the aim of this written report, several authors accept shown an clan between happiness and different prosocial behavior outcomes such as volunteering, charity donations, and helping others (e.thousand., Aknin et al. 2018; Appau and Churchill 2018; Dunn et al. 2008; Post 2005; Thoits and Hewitt 2001). Diener and colleagues have also pointed out that happiness may increase the likelihood to perform adaptive social behaviors. Indeed, people's happiness would seem to increase sociality, mating and creativity (Diener et al. 2015). A contempo study has shown that happiness derives from career success, and vice versa, it can also lead to improved outcomes in the workplace, thus pointing out that the hypothesis which claims that happiness could be an antecedent of such outcomes is plausible (Walsh et al. 2018). Based on these studies, happiness would seem to represent a relevant factor contributing to prosocial behavior; and appropriately to the evolution of the society (e.g., Aknin et al. 2018; Appau and Churchill 2018; Diener et al. 2015; Thoits and Hewitt 2001; Walsh et al. 2018). In this vein, Oishi and colleagues (2018) take recently provided compelling empirical evidence demonstrating that people's happiness is strongly related to income inequality. In item, information technology would seem that income inequality would make people less happy. Indeed, despite individuals' negative mental attitude towards taxation, it would seem that people are happier when paying taxes which, in turn, are aimed at reducing economic inequality (Oishi et al. 2018). Oishi et al. (2018) aspect this effect to a specific miracle, a and then-called "tax morale: feeling that i is a good denizen past paying taxes" (p. 9). Appropriately, this link betwixt happiness and willingness to reduce social inequality is directly opposed to the link betwixt SDO and willingness to conserve the status quo also every bit differences among groups. To the best of my knowledge, there is no empirical evidence showing that happiness could influence mental attitude towards immigrants. Thus, empirical research that takes these factors into business relationship could help us to explain some mechanisms underlying the well-established human relationship between social potency and negative reaction towards immigrants.

From a different line of enquiry, compelling evidence has shown that people with a liberal credo are happier than conservatives (i.e., a political ideology strongly related to SDO) (e.g., Wojcik et al. 2015). Pollock and colleagues have likewise pointed out a positive relationship between happiness and personality traits related to a liberal credo, such as extraversion or openness to experience (Pollock et al. 2016). Such a link has been supported in different studies (e.thou., Diener and Seligman 2002; Lauriola and Iani 2017; Tkach and Lyubomirsky 2006). Thus, in the present research using a very large sample, it has been supposed that social dominance orientation (an private disposition related to a conservative ideology) might exist negatively associated with happiness. The thought backside this supposition is that conservative attitudes, such equally social dominance, might have a function aimed at maintaining the status quo, which is hard to maintain in a world as globalized as our earth. Globalization boosts rapid changes and transformations and, accordingly, it might exist frustrating to see that every effort to maintain the condition quo falls apart. For example, the bourgeois political parties' attempts to prevent immigrants from inbound European countries ofttimes fail because it is impossible to foreclose such migrations towards these countries. Thus, social-dominant people could exist less happy to live in a society that does not reflect their demand to maintain the condition quo or in which they see a threat to the hierarchical order of society. Previous empirical inquiry would not seem to highlight happiness as a resource that could play a relevant role in the relationship between social dominance and negative reaction towards immigrants. Thus, the master aim of the nowadays study consists of shedding light on whether and how people'south social dominance could exist related to attitude towards immigrants through happiness.

The Nowadays Written report

Previous social psychology research has demonstrated that social authorisation negatively affects attitude towards immigrants because social-dominant people would tend to conserve the status quo and perceive immigrants as a threat to information technology (e.m., Costello and Hodson 2010, 2011; Guimond et al. 2010; Thomsen et al. 2008). More specifically, the status boundary enforcement hypothesis pointed out that people'southward social potency is related to negative reactions towards immigrants when they show willingness to assimilate into the dominant culture. Information technology is likely that, in a social-dominant view, such an effect could be explained by the perception of the threat that immigrants could get beyond the borders of the group to which they vest (Thomsen et al. 2008). On the other hand, recent compelling bear witness has shown that happiness tin can exist related to a willingness to reduce economic inequality (i.e., a vision of society related to low social dominance) and liberal ideologies (e.g., Oishi et al. 2018; Wojcik et al. 2015). Thus, cartoon on previous studies, this research is aimed at testing the following hypotheses: First, it is predicted that individuals showing higher levels of happiness would also prove a positive mental attitude towards immigrants compared to individuals with lower levels of happiness. 2d, it is predicted that SDO is related to happiness, which in plow, is related to attitude towards immigrants. Specifically, it has been hypothesized that greater SDO is related to negative attitude towards immigrants through a lower level of happiness. Finally, it is as well expected to replicate and corroborate the link between SDO and mental attitude towards immigrants using the European Social Survey (ESS) data that get in possible to robustly exam this association by using a very large sample.

two. Materials and Methods

2.ane. Participants

In this research, information from the seventh round of the ESS (2014) have been analyzed. This round has been chosen equally it focused specifically on measuring attitudes towards clearing. The ESS databases are freely available to researchers and contain measures of attitude towards immigrants, demographics and personality dispositions. The ESS (2014) round 7 data provide empirically grounded blended indexes every bit an option to analyze immigration attitudes. The ESS is a information source enabling the investigation of the issues well-nigh the clearing attitudes that are some of the most often used in bookish research. The population considered was composed of Eu citizens over the age of fifteen. For each of the European countries, respondents were selected past means of strict probability samples of the resident populations. Participants were interviewed using face-to-face up mode regarding different social issues including their attitudes towards immigration, social dominance and happiness (ESS 2014). The total sample was of forty,185 participants. Women made upwardly 53% of the sample (Mage = 49.28; SD = 18.74). Due to some missing values, the valid sample for the mediation model described herein was 35,126.

An overview, more details, and a full description of the blueprint of the survey (ESS) are reported at the post-obit spider web link: http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org.

two.ii. Measures

2.2.one. Social Dominance Orientation

The key index of orientation to equality—SDO—has been measured through the following item: "Would you lot say that some cultures are much better than others or that all cultures are equal?" (opposite coded). Respondents rated the extent to which they agreed with this statement (1 = Some cultures are much better than others; ii = All cultures are equal).

2.ii.2. Happiness

The index of happiness has been assessed through the following item: "How happy would you say you are?" Respondents rated the extent to which they agreed with this statement, on an 11-point scale, with the responses anchored at the ends with 0 (extremely unhappy) and x (extremely happy).

2.two.3. Attitude towards Immigrants

Such an alphabetize has been assessed through 3 items: "Would you say it is generally bad or good for [country]'s economy that people come to live here from other countries?" Respondents indicated their understanding with this statement, past an eleven-point scale, with the responses anchored at the ends (0 = Bad for the economic system–ten = Good for the economy). The following ii items were: "Would you say that [country]'southward cultural life is more often than not undermined or enriched by people coming to alive here from other countries?" (11-indicate scale response options: 0 = Cultural life undermined–10 = Cultural life enriched); "Is [country] made a worse or a ameliorate identify to alive by people coming to live hither from other countries?" (eleven-betoken scale response options: 0 = Worse place to live–10 = Better place to live). This index has been calculated as the aggregated index by summing upwards all responses to all items in the alphabetize. Cronbach's alpha of this sample was 0.85.

3. Results

To investigate the relationships between SDO, happiness and mental attitude towards immigrants, the goose egg-gild correlations among these variables have been computed (encounter Table ane). The results of the nowadays inquiry showed that SDO was significantly negatively related to both happiness and attitude towards immigrants. Finally, individuals' happiness was significantly and positively associated with a favorable mental attitude towards immigrants (see Table 1).

As expected, the association of happiness with attitude towards immigrants was supported past a multiple regression model where attitude towards immigrants score was regressed on participants' happiness (β = 0.233, p < 0.001; B unstandardized = 0.780, 95% CI = 0.747 to 0.813). In the model, age and gender (women coded equally i and men coded equally 2) were entered as covariates and they also showed a pregnant effect with men and the young showing a more than positive mental attitude towards immigrants (gender β = 0.022, p < 0.001; B unstandardized = 0.272, 95% CI = 0.148 to 0.396; age β = −0.064, p < 0.001; B unstandardized = −0.022, 95% CI = −0.025 to -0.018).

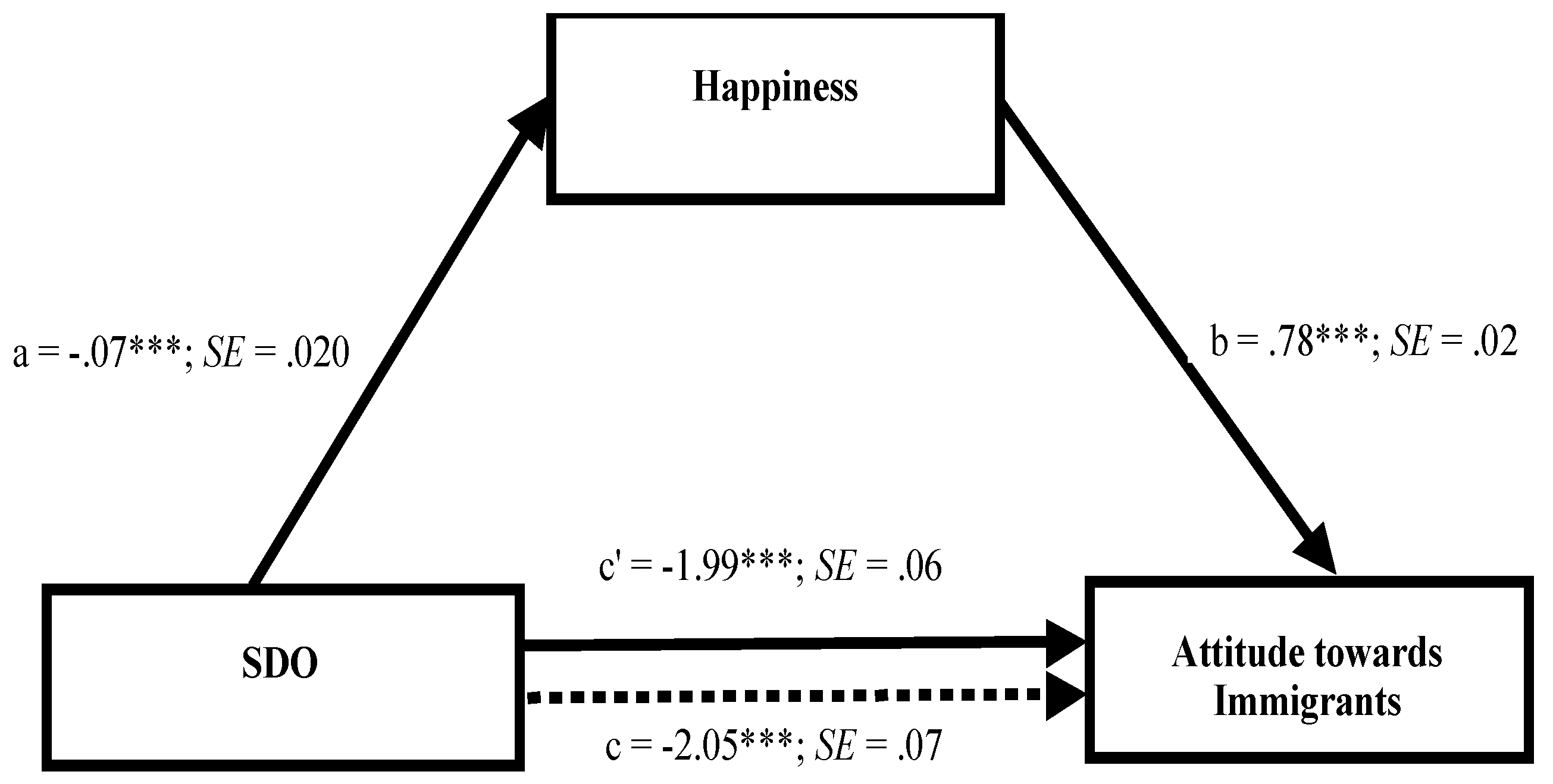

To empathise the mechanisms underlying the relationships between SDO, happiness and mental attitude towards immigrants, the Process macro for SPSS has been used (see Hayes 2013; for more details), which tested the arbitration hypothesis (Hayes 2009; Preacher and Hayes 2008). Hayes and Scharkow (2013) have claimed that the bootstrapping procedure is the nearly trustworthy method of assessing the effects of mediation models. The arbitration model included SDO as the independent variable, happiness as the mediator, and attitude towards immigrants as the dependent variable. Such a model was estimated to derive the total, direct and indirect associations of SDO with attitude towards immigrants through happiness. The model estimated the indirect result of SDO on attitude towards immigrants, quantified as the product of the ordinary to the lowest degree squares (OLS) regression coefficient estimating happiness from SDO (path a in Figure one) and the OLS regression coefficient estimating attitude towards immigrants from happiness, decision-making for SDO (path b in Figure 1). A bias-corrected bootstrap-confidence interval (CI) for the production of these paths that does non include cypher provides evidence of a significant indirect issue (see MacKinnon et al. 2000; Preacher and Hayes 2008; Hayes 2009, 2013; for more than details). Using the PROCESS macro with 5000 bootstrap samples, the results of the present research revealed a pregnant negative indirect effect of SDO on attitude towards immigrants through happiness (betoken estimate = −0.057; 95% CI = −0.088 to −0.027).

Since participants' gender and age could be related to attitude towards immigrants, then a mediating model which included gender (women coded as 1 and men coded as ii) and age as covariates has been tested. The dependent, independent and mediator variables were the aforementioned every bit in the previous model (meet Figure one for more details). The relationships between SDO, happiness and attitude towards immigrants did not substantially change after controlling for the effect of these covariates (indicate estimate = −0.05; 95% CI = −0.076 to −0.017). In line with previous results, the model showed a significant positive consequence of gender on attitude towards immigrants (β = 0.029, p < 0.001; B unstandardized = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.23 to 0.48), with men showing a more positive attitude towards immigrants. A significant negative consequence of age on attitude towards immigrants has besides been confirmed (β = −0.058, p < 0.001; B unstandardized = −0.020, 95% CI = −0.023 to −0.016), with older people showing negative attitude towards immigrants.

4. Discussion

The present research was aimed to investigate two principal purposes. Showtime, this study has sought to institute a positive link betwixt happiness and a favorable attitude towards immigrants. The 2d purpose of the present research was to point out whether social dominance was related to attitude towards immigrants through happiness. Finally, admitting in previous enquiry, an clan betwixt SDO and negative attitude towards immigrants has already been established, a further aim of this study has been to approve this relationship through a very large sample (Costello and Hodson 2010, 2011; Guimond et al. 2010; Thomsen et al. 2008). Taken together, the results of the nowadays research provide support for the hypotheses of the study. More specifically, it shows a positive link between people'southward happiness and a favorable mental attitude towards immigrants. Such a link is relevant considering according to Oishi and colleagues' perspective, 1 might claim that happiness may represent a relevant resource to reduce inequality as well as promote a favorable attitude towards immigrants (Oishi et al. 2018). In particular, in the nowadays study it has been seen that people'southward happiness plays a relevant role in the relationship between SDO and negative reactions towards immigrants. In fact, the results of the nowadays research firstly prove that a negative link between SDO and mental attitude towards migrants could be explained from lower levels of citizens' happiness. An overarching message of this study is that people who are higher in happiness show a more favorable attitude towards immigration and a more than egalitarian opinion in social club. This represents a novel insight, as happiness can be a factor susceptible to public policies and interventions. Indeed, one could suppose that policy determination makers may counteract negative reactions towards immigration and populism related to this phenomenon, for example, past acting promptly on citizens' happiness via policies aimed at fostering such a factor. For instance, some public policies promoting unemployment protection and welfare benefits might enhance and support people's happiness. Some authors argue that people are more satisfied when regime actively intervenes in the market economy, for example, by modifying the outcome of it (east.grand., Flavin and Radcliff 2009; Flavin et al. 2011; Radcliff and Shufeldt 2016). It would seem that government efforts in this direction would foster happiness across society at large, and non just in less-privileged people. Moreover, public intervention efforts to protect citizens from the instability of the market economy would seem to exist associated with greater happiness (come across Flavin et al. 2011; Radcliff and Shufeldt 2016; for more details). Thus, such a factor could represent a lever to promote unlike positive social outcomes such as greater equality, counteracting populism, as well equally preventing negative reactions and prejudice towards immigrants.

From a unlike line of enquiry, some authors have pointed out a significant relationship betwixt mindfulness and happiness, also as social authority orientation (e.g., Brown and Kasser 2005; Hollis-Walker and Colosimo 2011; Jazaieri et al. 2014; Panno et al. 2018). In this vein, Lim et al. (2015) have shown that a mindfulness meditation preparation self-administered via smart technologies was constructive in determining more compassionate beliefs towards strangers (Lim et al. 2015). Keeping in mind that mindfulness is negatively related to SDO and positively to happiness (Brown and Kasser 2005; Hollis-Walker and Colosimo 2011; Jazaieri et al. 2014; Panno et al. 2018), one might expect that mindfulness preparation could exist helpful to reduce negative reactions towards immigrants and the tendency to back up the inequality expressed past social-dominant people. Thus, mindfulness training could be adopted with the purpose of coping with migration problems. This is encouraging in terms of the applied interventions of these results, even though time to come studies are needed to shed light on such a field. In this vein, some authors have as well shown that an emotion regulation strategy that is strongly related to happiness (i.e., cognitive reappraisal; Gross and John 2003) can stand for a helpful resource to cope with relevant social issues such as climate change and intractable conflicts (due east.yard., Israeli–Palestinian conflict; Gross et al. 2013; Halperin et al. 2013; Halperin 2014; Panno et al. 2015). Future studies could exam whether well-established interventions aimed at the enhancement of such an emotion regulation strategy might also be effective in coping with the clearing issues (see Halperin et al. 2013; Halperin 2014; for more details).

Fifty-fifty though this research offers notable strengths, some limitations should exist considered when drawing conclusions from it. First, although a very large sample has been used to shed light on the relationships between SDO, happiness and attitude towards immigrants, the mediating role of happiness needs to be supported by further empirical evidence. Thus, time to come longitudinal studies investigating causal mechanisms underlying these relationships are needed. Future studies should as well seek to replicate such results in an experimental setting trying to manipulate happiness every bit well as using implicit measures to assess mental attitude towards immigrants. It is true that the cross-sectional nature of the studies does not allow causal inferences; nevertheless, the results of the present research provide relevant insights into the relationships between SDO, happiness and attitude towards immigration. Second, some studies have shown happiness to be related to some personality dispositions that could play a further part in these relationships (east.g., Pollock et al. 2016). It was beyond the telescopic of the current study to investigate all of these, but nosotros cannot rule out that some of these might influence these relationships. Thus, hereafter studies should have into account these factors when examining such relationships.

To summarize, this piece of work extends previous research in the following ways: Get-go, it shows a positive link betwixt happiness and a favorable attitude towards immigrants. Second, the findings of this research shed light on the relationship between social dominance and negative reactions towards immigration showing that happiness plays a primal role in it. Third, even though previous studies showed a link between social dominance orientation and mental attitude towards immigrants, these results add empirical evidence corroborating such a relationship through a very large sample (east.g., Costello and Hodson 2010, 2011; Guimond et al. 2010; Thomsen et al. 2008).

In conclusion, the nowadays study advanced a model illustrating a relevant and wide potential mechanism underlying the association betwixt SDO and mental attitude towards immigration. The results of the present research increase our knowledge near social say-so theory (e.one thousand., Pratto et al. 1994; Pratto et al. 2006) and are also relevant for studies that rely on happiness to predict social outcomes (e.k., Aknin et al. 2018; Diener et al. 2015; Oishi et al. 2018; Radcliff and Shufeldt 2016). Broadly speaking, the results of this research can hope novel insight into these connections across diverse fields including social and positive psychology, as well as political science. More and more studies are needed to make full the gap among these disciplines, but the intersection between psychological and political science can represent a fruitful avenue to cope with relevant social issues peculiar to our time (eastward.yard., climate change, migration, etc.). The present research is an attempt in this direction suggesting that a dominant view, whether it pertains to the potent or weak, does not fit well with a happiness stance. Such a misfit holds the potential to be a powerful tool to promote equality also as reduce bigotry in guild at large.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aknin, Lara B., Julia W. Van de Vondervoort, and Kiley J. Hamlin. 2018. Positive feelings reward and promote prosocial beliefs. Current Opinion in Psychology 20: 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appau, Samuelson, and Sefa A. Churchill. 2018. Charity, Volunteering Type and Subjective Wellbeing. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. Advance on line publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownish, Kirk Due west., and Tim Kasser. 2005. Are psychological and ecological well-existence uniform? The function of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Social Indicators Research 74: 349–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Andrew E., Sarah Flèche, Richard Layard, Nattavudh Powdthavee, and George Ward. 2018. The Origins of Happiness: The Scientific discipline of Well-Being over the Life Course. Princeton: University Printing. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, Kimberly, and Gordon Hodson. 2010. Exploring the roots of dehumanization: The role of creature—Human similarity in promoting immigrant humanization. Grouping Processes & Intergroup Relations thirteen: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, Kimberly, and Gordon Hodson. 2011. Social say-so-based threat reactions to immigrants in need of assistance. European Journal of Social Psychology 41: 220–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, and Robert Biswas-Diener. 2002. Will money increase subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research 57: 119–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, and Martin E. Seligman. 2002. Very happy people. Psychological Scientific discipline thirteen: 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, Ed, Satoshi Kanazawa, Eunkook K. Suh, and Shigehiro Oishi. 2015. Why people are in a generally expert mood. Personality and Social Psychology Review xix: 235–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, Ed, Sarah D. Pressman, John Hunter, and Desiree Delgadillo-Chase. 2017. If, why, and when subjective well-being influences health, and futurity needed research. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 9: 133–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, Elizabeth W., Lara B. Aknin, and Michael I. Norton. 2008. Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science 319: 1687–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESS. 2014. ESS7 - 2014 Data Download. Available online: http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/download.html?r=7 (accessed on 3 June 2018).

- EUROSTAT. 2017. Statistiche sulle migrazioni internazionali e sulle popolazioni di origine straniera. Available online: http://ec.europa.european union/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics/it (accessed on 3 June 2018).

- Flavin, Patrick, and Benjamin Radcliff. 2009. Public policies and suicide rates in the American states. Social Indicators Enquiry 90: 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavin, Patrick, Alexander C. Pacek, and Benjamin Radcliff. 2011. Country Intervention and Subjective Well-Being in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Politics & Policy 39: 251–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, James J., and Oliver P. John. 2003. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for bear upon, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85: 348–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, James J., Eran Halperin, and Roni Porat. 2013. Emotion regulation in intractable conflicts. Electric current Directions in Psychological Science 22: 423–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimond, Serge, Pierre De Oliveira, Rodolphe Kamiesjki, and Jim Sidanius. 2010. The trouble with assimilation: Social authorisation and the emergence of hostility confronting immigrants. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 34: 642–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, Eran. 2014. Emotion, emotion regulation, and conflict resolution. Emotion Review six: 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, Eran, Roni Porat, Maya Tamir, and James J. Gross. 2013. Can emotion regulation modify political attitudes in intractable conflicts? From the laboratory to the field. Psychological Science 24: 106–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2009. Across Baron and Kenny: Statistical arbitration analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs 76: 408–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Procedure Analysis. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Michael Scharkow. 2013. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Scientific discipline 24: 1918–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollis-Walker, Laurie, and Kenneth Colosimo. 2011. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and happiness in non-meditators: A theoretical and empirical examination. Personality and Individual Differences 50: 222–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazaieri, Hooria, Kelly McGonigal, Thupten Jinpa, James R. Doty, James J. Gross, and Philippe R. Goldin. 2014. A randomized controlled trial of compassion cultivation training: Effects on mindfulness, affect, and emotion regulation. Motivation and Emotion 38: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebb, Andrew T., Louis Tay, Ed Diener, and Shigehiro Oishi. 2018. Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the earth. Nature Human Behaviour ii: 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauriola, Marco, and Luca Iani. 2017. Personality, positivity and happiness: A mediation analysis using a bifactor model. Journal of Happiness Studies 18: 1659–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Daniel, Paul Condon, and David DeSteno. 2015. Mindfulness and compassion: An examination of mechanism and scalability. PLoS ONE 10: e0118221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, David P., Jennifer Fifty. Krull, and Chondra Chiliad. Lockwood. 2000. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science i: 173–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastekaasa, Arne. 1994. Marital status, distress, and well-being: An international comparison. Periodical of Comparative Family unit Studies 6: 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Naseem, Khalida. 2018. Task Stress, Happiness and Life Satisfaction: The Moderating Role of Emotional Intelligence Empirical Study in Telecommunication Sector Pakistan. Journal of Social Science 4: 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, Shigehiro, Kostadin Kushlev, and Ulrich Schimmack. 2018. Progressive taxation, income inequality, and happiness. American Psychologist 73: 157–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panno, Angelo, Giuseppe Carrus, Fridanna Maricchiolo, and Lucia Mannetti. 2015. Cerebral reappraisal and pro-environmental behavior: The role of global climatic change perception. European Journal of Social Psychology 45: 858–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, Angelo, Mauro Giacomantonio, Giuseppe Carrus, Fridanna Maricchiolo, Sabine Pirchio, and Lucia Mannetti. 2017. Mindfulness, pro-environmental behavior, and belief in climate alter: The mediating role of social authorisation. Surroundings and Behavior. Advance on line publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Noah C., Amy E. Noser, Christopher J. Holden, and Virgil Zeigler-Loma. 2016. Do orientations to happiness mediate the associations between personality traits and subjective well-being? Journal of Happiness Studies 17: 713–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, Stephen G. 2005. Altruism, happiness, and health: It's good to exist proficient. International Periodical of Behavioral Medicine 12: 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratto, Felicia, Jim Sidanius, Lisa M. Stallworth, and Bertram F. Malle. 1994. Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67: 741–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pratto, Felicia, Jim Sidanius, and Shana Levin. 2006. Social authorization theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. European Review of Social Psychology 17: 271–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew F. Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods forty: 879–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radcliff, Benjamin, and Gregory Shufeldt. 2016. Direct democracy and subjective well-existence: The initiative and life satisfaction in the American States. Social Indicators Research 128: 1405–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, Jim, and Felicia Pratto. 2001. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius, Jim, Felicia Pratto, and Lawrence Bobo. 1994a. Social authorization orientation and the political psychology of gender: A example of invariance? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67: 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, Jim, Felicia Pratto, and Michael Mitchell. 1994b. In-grouping identification, social dominance orientation, and differential intergroup social allotment. The Journal of Social Psychology 134: 151–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, Jim, Nour Kteily, Jenniffer Sheehy-Skeffington, Arnold K. Ho, Chris Sibley, and Bart Duriez. 2013. You're inferior and not worth our concern: The interface between empathy and social authorization orientation. Journal of Personality 81: 313–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoits, Peggy A., and Lyndi North. Hewitt. 2001. Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Wellness and Social Behavior 42: 115–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, Lotte, Eva G. Light-green, and Jim Sidanius. 2008. We will hunt them down: How social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism fuel ethnic persecution of immigrants in fundamentally different ways. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44: 1455–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkach, Chris, and Sonya Lyubomirsky. 2006. How do people pursue happiness?: Relating personality, happiness-increasing strategies, and well-being. Periodical of Happiness Studies vii: 183–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Lisa C., Julia K. Boehm, and Sonya Lyubomirsky. 2018. Does Happiness Promote Career Success? Revisiting the Evidence. Journal of Career Cess. Advance on line publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcik, Sean P., Arpine Hovasapian, Jesse Graham, Matt Motyl, and Peter H. Ditto. 2015. Conservatives report, but liberals display, greater happiness. Scientific discipline 347: 1243–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1. Path coefficients for mediation analysis in the Report. Note: Dotted line denotes the effect of social authorisation orientation on attitudes towards immigrants, when happiness is not included as a mediator. a, b, c and c′ are unstandardized OLS regression coefficients. *** p < 0.001.

Figure 1. Path coefficients for mediation assay in the Study. Annotation: Dotted line denotes the effect of social dominance orientation on attitudes towards immigrants, when happiness is non included equally a mediator. a, b, c and c′ are unstandardized OLS regression coefficients. *** p < 0.001.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations among variables investigated in the Study.

Tabular array 1. Ways, standard deviations and intercorrelations among variables investigated in the Report.

| 1 | ii | iii | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 SDO—Social Dominance Orientation | one | ||

| 2 Happiness | −0.019 *** | 1 | |

| 3 Attitudes towards Immigrants | −0.163 *** | 0.238 *** | ane |

| 1000 (SD) | ane.43 (0.49) | 7.39 (1.90) | fifteen.64 (6.27) |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed nether the terms and conditions of the Artistic Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/7/8/126/htm

0 Response to "Free Peer Review Article on Social Dominance Theory"

Post a Comment